The birth of a baby with cleft lip and/or palate can be devastating. Dorothy Lepkowska speaks to a family which has lived through the challenges of childhood treatment and supporting a child with the condition.

Liz Laney will never forget the look on her parents’ faces when she introduced them to her baby son – their first grandson – in the hospital ward.

“I can only describe it as one of devastation,” she said. “We had warned them that Dominic was born with a cleft lip, but they simply weren’t prepared for how he looked. My mother began to cry, but my father just picked him, hugged him close and kissed his little forehead.

“His reaction was hugely comforting to me, not just for the acceptance of our poor little boy but also because I knew we were going to get through the long road ahead with the love of our family. Seeing your baby born with a facial deformity is devastating but, to us, he was the most beautiful baby. We were sure he was trying to smile at us and let us know it was all going to be ok.”

Genetic and environmental factors

Dominic, who is now in his 30s and married with children, was one of more than 1,200 babies born in the UK every year with a cleft lip and/or palate.

Worldwide, around one in 700 children are born with the condition – the most common craniofacial abnormality among infants.

The causes of cleft lip and palate are not really clear, but medical experts believe it could be a combination of different genetic and environmental factors, which cannot be prevented or predicted.

If there is cleft in the family, then a child is more likely to be born with a cleft.

Depending on the cause, a parent with a cleft has a likelihood of up to 50% of a child having the condition, though it can be as low as 2%. Genetic testing is available if families want to work out the possibility of having a child with cleft.

Sometimes the condition is caused by a syndrome when several symptoms happen all at once. Whatever the reason, it is rarely the fault of the parents nor anything they have done. It is something that, sadly, just affects some babies.

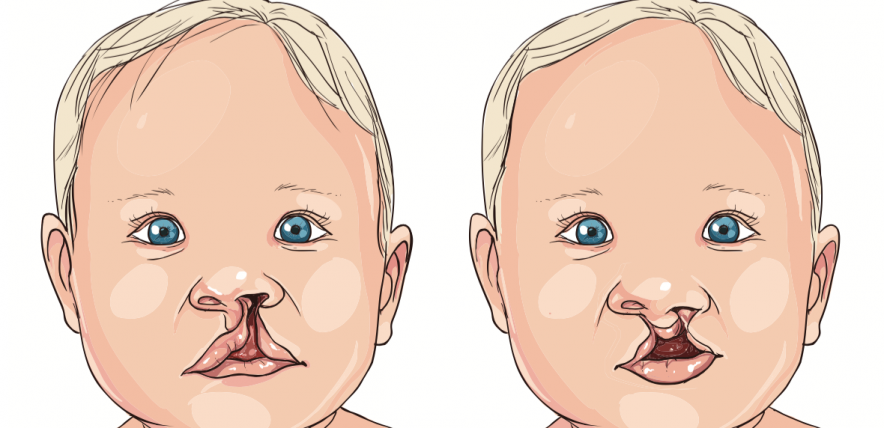

Varying levels of severity

Cleft lip and palate can take different forms and levels of severity. With a cleft lip it can range from a small notch in the lip to a complete separation of the upper lip extending into the nose.

Sometimes the lip has two gaps, which is known as a bilateral cleft. The condition can also affect the gums affected the growth of teeth.

Cleft palate is a gap in the roof of the mouth and can affect both the soft palate at the back of the mouth, and the hard palate towards the front.

Difficulty feeding

One of the main difficulties affecting babies with a cleft is feeding. When breast or bottle feeding, babies need to be able to form a vacuum inside their mouths and to position their tongue to be able to draw milk. This natural reflect involves sucking, breathing and swallowing.

Some babies with a cleft are not able to form this vacuum because of the gap in their lip and/or palate. Experts have likened it to trying to drink through a straw full of holes.

However, special bottles are available to help them overcome these problems.

Condition can be detected by scan then treated

Liz was completely unprepared for Dominic’s condition, which was discovered only after he was born. There had been no prior indication and there was no antenatal diagnosis, as is now possible with more modern scanning technology. She had a problem-free pregnancy, did not smoke or drink and was careful about her diet.

Parents whose children are faced with this prospect now can expect to embark on a treatment pathway, with the support of a local cleft team.

How this works will vary around the UK, but it will involve specialist paediatric services and will include medical experts who have expertise in your children’s particular needs – such as speech or hearing therapists.

There are also support groups for parents and children as they grow older, including counselling services.

Repair surgery usually begins once the child is older than three months, but this will need to be reviewed and possibly adjusted as he or she grows older at appropriate times in their physical and emotional development.

“I had the support of a fantastic GP, local paediatric services and we made friends with another family not too far away who were going through the same thing, so the boys grew up together, which normalised their condition,” Liz said. “As we went through treatment we met many families with children with cleft problems, some very much worse than Dominic’s.

“He had the first of his repair surgeries at a few months’ old, and a couple more as he grew up. He has a scar, but it has never bothered him or held him back in any way. Neither of his children has the condition, and to this day we are not sure why he does.

“It was a frightening diagnosis at the time, and we seriously considered whether to have any more children, but our other son and daughter were born healthy and well. There is a great deal of expertise out there and people know so much more now than we did then, and treatments have evolved.”

Further reading:

What is a cleft lip and palate?